A Search and Rescue boat's critical electronics

As a welcome change from his usual duties, Howie relaxes at the helm of Royal Canadian Marine Search and Rescue (RCMSAR) Unit 1's Falkens class boat -- Craig Rae Spirit. More often he's face down in the water on a training exercise anxiously awaiting rescue from the ocean near Vancouver. Howie is integral to Unit 1's training program which includes: emergency procedures, first-aid, seamanship, vessel handling, teamwork, electronic navigation and the use of marine electronics. Let's take a closer look at the training needed to use some of the gear on SAR 1, along with how and why it is used on a search and rescue mission...

As a welcome change from his usual duties, Howie relaxes at the helm of Royal Canadian Marine Search and Rescue (RCMSAR) Unit 1's Falkens class boat -- Craig Rae Spirit. More often he's face down in the water on a training exercise anxiously awaiting rescue from the ocean near Vancouver. Howie is integral to Unit 1's training program which includes: emergency procedures, first-aid, seamanship, vessel handling, teamwork, electronic navigation and the use of marine electronics. Let's take a closer look at the training needed to use some of the gear on SAR 1, along with how and why it is used on a search and rescue mission...

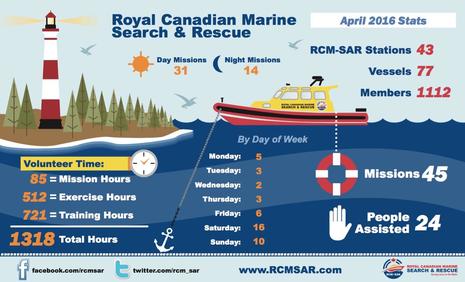

RCMSAR crews spend a lot of time training. You can see from April's volunteer time that the organization's members spent about 5% of the time on missions and the rest actively training. In my March Panbo entry I explained how RCMSAR and the Canadian Coast Guard work together as primary responders on Canada's west coast. New volunteer crew members need a minimum of a radio operator's certificate, pleasure craft operators card and completed first aid course to be eligible to train to become RCMSAR crew. From then on they receive peer training within the unit along with taking some of the external training courses shown on the RCMSAR website.

RCMSAR crews spend a lot of time training. You can see from April's volunteer time that the organization's members spent about 5% of the time on missions and the rest actively training. In my March Panbo entry I explained how RCMSAR and the Canadian Coast Guard work together as primary responders on Canada's west coast. New volunteer crew members need a minimum of a radio operator's certificate, pleasure craft operators card and completed first aid course to be eligible to train to become RCMSAR crew. From then on they receive peer training within the unit along with taking some of the external training courses shown on the RCMSAR website.

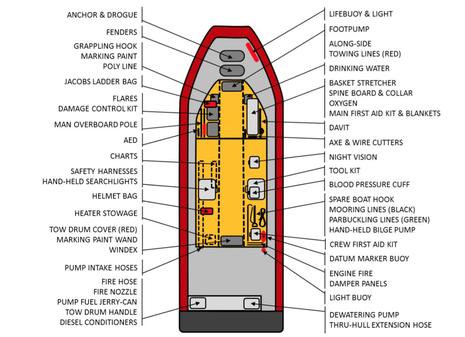

Guessing that you probably have little knowledge of how SAR crews operate or what equipment we use, here's a chance to virtually come aboard a 36 foot, 40 knot capable aluminum jet boat loaded with some pretty cool technology.

Here's the layout of the antennas and equipment on the roof of our sealed and self-righting rescue craft. Not that these electronics would live through a capsize, but in stormy weather we'd survive in our sealed cabin while seatbelted in shock absorbing seats. From front to back is a Whelen loudhailer speaker connected inside to a Raymarine 30 Watt 430 loudhailer (no longer made) at the navigation seat. This is a great attention getter and primarily used for initial contact with a vessel before we have established two way communication via VHF radio or are close enough to shout. Behind the speaker is a FLIR T-453 thermal camera which is used for night search along with the ACR search lights next to it. Further back amongst various VHF/AIS antennas is a Ray open array radar scanner. Topping it all off are the four antennas for the Taiyo radio direction finder (RDF)...

Here's the layout of the antennas and equipment on the roof of our sealed and self-righting rescue craft. Not that these electronics would live through a capsize, but in stormy weather we'd survive in our sealed cabin while seatbelted in shock absorbing seats. From front to back is a Whelen loudhailer speaker connected inside to a Raymarine 30 Watt 430 loudhailer (no longer made) at the navigation seat. This is a great attention getter and primarily used for initial contact with a vessel before we have established two way communication via VHF radio or are close enough to shout. Behind the speaker is a FLIR T-453 thermal camera which is used for night search along with the ACR search lights next to it. Further back amongst various VHF/AIS antennas is a Ray open array radar scanner. Topping it all off are the four antennas for the Taiyo radio direction finder (RDF)...

I could probably train someone to use the Taiyo RDF in under ten minutes. Switch it on, select a channel to listen to and then follow the red LED you see in the bottom left corner of the display. The idea is to try to keep the LED centered under the green dot by turning the boat towards the signal. The unit is always in a heads-up orientation. In the above example, if you turn to port 135 degrees (360 - 225) you should be pointing towards your broadcast source. You can see it tuned to channel 16 which is sometimes used to search for those pesky open mike situations where kids are fooling around or a transmit button is stuck.

I could probably train someone to use the Taiyo RDF in under ten minutes. Switch it on, select a channel to listen to and then follow the red LED you see in the bottom left corner of the display. The idea is to try to keep the LED centered under the green dot by turning the boat towards the signal. The unit is always in a heads-up orientation. In the above example, if you turn to port 135 degrees (360 - 225) you should be pointing towards your broadcast source. You can see it tuned to channel 16 which is sometimes used to search for those pesky open mike situations where kids are fooling around or a transmit button is stuck.

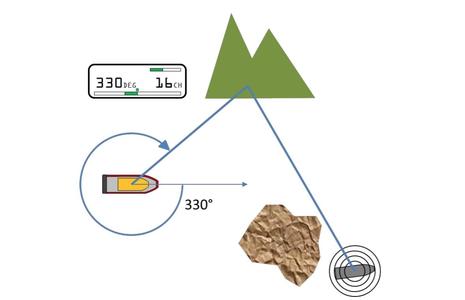

One of the difficulties of Howe Sound where we usually operate is the tall mountains which reflect signals in such a way to sometimes make it confusing to easily follow a signal. The diagram taken from our standard operating procedures manual shows how mountains can bounce a signal and cause confusion. Trial and error and patience usually gets results. We also use the RDF to hone in and retrieve our vessel's Novatech datum marker buoy (DMB) which transmits on VHF channel 15 with a maximum eight mile range.

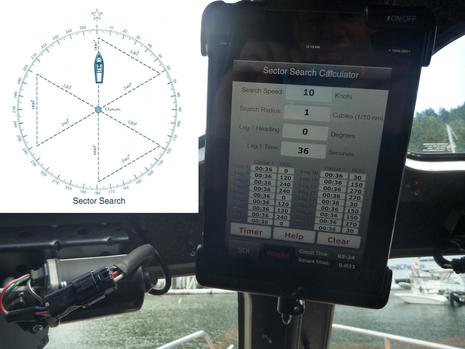

The DMB shown can be a very important piece of equipment on a tasking and is usually used to establish the starting point of a sector search based on a last known position that we have a high degree of confidence in. There are other kinds of searches we do including creeping line, parallel track, barrier and expanding square. It is only the sector search that requires us to return to our datum (start point) on every third leg, and the datum needs to move with the current and the wind hopefully like the person or object we are searching for.

The DMB shown can be a very important piece of equipment on a tasking and is usually used to establish the starting point of a sector search based on a last known position that we have a high degree of confidence in. There are other kinds of searches we do including creeping line, parallel track, barrier and expanding square. It is only the sector search that requires us to return to our datum (start point) on every third leg, and the datum needs to move with the current and the wind hopefully like the person or object we are searching for.

The question that trainees most often ask is why not use the chartplotter to drive an exact course over ground? This would make it easier than using timed search legs at a set speed based on manual computation, but more effective search patterns are scribed out on the surface of the ocean, not on the earth. If we were searching for an object fixed to the bottom then GPS would be useful. The water is moving from currents and wind and therefore so is what we are searching for. Rescue Command's computer modeling can give some idea as to water direction and speed but it is not as accurate as using the on-scene DMB's behavior as a direct reference point.

Speed is of the essence so if we are conducting a sector search we arrive to the tasked position and drop the DMB and then calculate our leg times based on our Coxswain's decision regarding an appropriate search speed and radius, which is influenced by visibility and weather conditions. In the past we used manual calculation and a stopwatch to run these searches. Now we use an iPhone/Android app I wrote for RCMSAR -- shown above our navigation seat -- which does the calculation and runs a countdown timer which can be reset as you pass back through datum. Our unit has found it quicker and easier to run searches using an iPad which also stores maps showing local place names not found on marine charts.

Speed is of the essence so if we are conducting a sector search we arrive to the tasked position and drop the DMB and then calculate our leg times based on our Coxswain's decision regarding an appropriate search speed and radius, which is influenced by visibility and weather conditions. In the past we used manual calculation and a stopwatch to run these searches. Now we use an iPhone/Android app I wrote for RCMSAR -- shown above our navigation seat -- which does the calculation and runs a countdown timer which can be reset as you pass back through datum. Our unit has found it quicker and easier to run searches using an iPad which also stores maps showing local place names not found on marine charts.

Before finishing my discussion of search tools I should mention the older pair of ITT G3 night vision goggles shown on our equipment map under the helm seat along with the hand-held search lights located amid-ship on the port side. These are typically used by two crew on the aft deck during a search to scan the ocean to the side and rear of the vessel. The helmsman and navigator also have controls for the roof mounted ACR search lights.

Before finishing my discussion of search tools I should mention the older pair of ITT G3 night vision goggles shown on our equipment map under the helm seat along with the hand-held search lights located amid-ship on the port side. These are typically used by two crew on the aft deck during a search to scan the ocean to the side and rear of the vessel. The helmsman and navigator also have controls for the roof mounted ACR search lights.

The twin 450 horsepower Volvo diesels on our boat are quite loud so it is crucial to have an easy way for the crew to communicate. One of the most critical and expensive electronics systems on the boat is our David Clark wired and wireless communication system, which are used by many search and rescue organizations. The next time you watch a Hollywood movie showing the military or search crews in action you'll probably see David Clark headsets being worn. Aside from the five wired stations overhead we also use the wireless universal gateway along with two wireless headsets for crew to move about the deck with.

The twin 450 horsepower Volvo diesels on our boat are quite loud so it is crucial to have an easy way for the crew to communicate. One of the most critical and expensive electronics systems on the boat is our David Clark wired and wireless communication system, which are used by many search and rescue organizations. The next time you watch a Hollywood movie showing the military or search crews in action you'll probably see David Clark headsets being worn. Aside from the five wired stations overhead we also use the wireless universal gateway along with two wireless headsets for crew to move about the deck with.

Crews are trained to use a closed-loop method of communications. This is to ensure that what has been communicated has been received loud and clear. It works something like this:

Navigator: "Turn 25 degrees to port!"

Helm: "25 degrees to port"

Wired directly into the headset system is the output from both Icom M604 DSC capable VHF radios which are usually tuned to VHF 16 and the channel we use to communicate with Coast Guard radio and other SAR Vessels. To transmit we use the microphones directly attached to the radios.

By accident on the day I wanted to shoot some of the photos for this entry we received a tasking when I was five minutes from the boat. There was a report of a possible overturned vessel about 11 miles from our station with a very vague location reported by a car on the highway at quite a distance. After finding nothing and being stood down by Rescue Center I quickly took the above photo of the helm controls.

By accident on the day I wanted to shoot some of the photos for this entry we received a tasking when I was five minutes from the boat. There was a report of a possible overturned vessel about 11 miles from our station with a very vague location reported by a car on the highway at quite a distance. After finding nothing and being stood down by Rescue Center I quickly took the above photo of the helm controls.

Bottom right is the bucket controls for the waterjets and going counter-clockwise are the trim tab and wired headset controls. The Volvo engine displays are on top of the dash next to the Raymarine ST70 display. Yes that's 707 feet faintly showing. We had just searched the deepest part of Howe Sound which is over 900 feet deep. The person driving the boat is trained to only glance at the instruments while maintaining vigilant watch out the front window. Navigation duties are owned by seats 2 and 3...

The seat to the left of the helm is what we call seat 2 and is the primary navigation seat. It is usually setup as shown with the (now "legacy") Raymarine E90w multifunction displays configured with chart on top and radar below. Under cover is the FLIR thermal camera control and to the right, the VHF, the loudhailer and RDF. This is the seat that typically works the radio and provides course information to the driver except in close quarter night navigation where seat 3 (radar) will issue navigation commands. During a night search the lower display can be switched to show camera imagery from the FLIR night vision camera. In practice the FLIR is seldom used on its own; it is used to augment the use of search lights because of its comparatively limited field of view.

The seat to the left of the helm is what we call seat 2 and is the primary navigation seat. It is usually setup as shown with the (now "legacy") Raymarine E90w multifunction displays configured with chart on top and radar below. Under cover is the FLIR thermal camera control and to the right, the VHF, the loudhailer and RDF. This is the seat that typically works the radio and provides course information to the driver except in close quarter night navigation where seat 3 (radar) will issue navigation commands. During a night search the lower display can be switched to show camera imagery from the FLIR night vision camera. In practice the FLIR is seldom used on its own; it is used to augment the use of search lights because of its comparatively limited field of view.

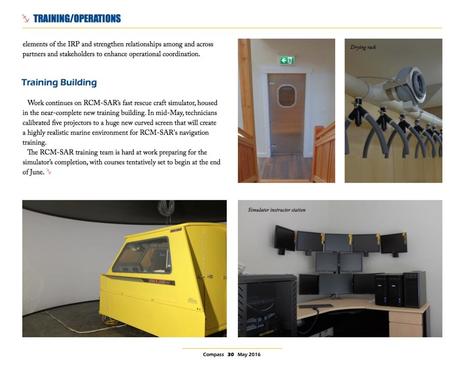

Seat 3 behind the helm is primarily used for radar watch. Under the multifunction display just above the second FLIR control you'll see an Icom F521 VHF/UHF transceiver specifically for communicating with land based SAR. If you look closely at the center of the screen you'll see the variable range marker (VRM) set to two tenths of a mile (2 cables). At night when we are navigating close to rocky shorelines in our area we often move at 30 knots plus. It is critical for seat 3 to guide the boat by touching the edge of the VRM bubble to the shoreline and issuing quick turn commands to the helmsman. It's a skill that takes practice and training learned on our SARNav 1 & 2 courses both on water and in a state of the art simulator.

Seat 3 behind the helm is primarily used for radar watch. Under the multifunction display just above the second FLIR control you'll see an Icom F521 VHF/UHF transceiver specifically for communicating with land based SAR. If you look closely at the center of the screen you'll see the variable range marker (VRM) set to two tenths of a mile (2 cables). At night when we are navigating close to rocky shorelines in our area we often move at 30 knots plus. It is critical for seat 3 to guide the boat by touching the edge of the VRM bubble to the shoreline and issuing quick turn commands to the helmsman. It's a skill that takes practice and training learned on our SARNav 1 & 2 courses both on water and in a state of the art simulator.

In 2004 RCMSAR secured a grant to develop the world's first fast rescue craft simulator which became a reality in 2007. As the pictures from RCMSAR's latest Compass Newsletter show, the simulator has just been moved and upgraded and is expected to be operational for RCMSAR and other organizations to train on by the end of June. RCMSAR's head office recently purchased the former Glenairley waterfront estate in East Sooke on Vancouver Island. Having completed SARNav 1, I can attest to the fact that training is both challenging and fun. When you are inside you totally forget you are in a simulator.

In 2004 RCMSAR secured a grant to develop the world's first fast rescue craft simulator which became a reality in 2007. As the pictures from RCMSAR's latest Compass Newsletter show, the simulator has just been moved and upgraded and is expected to be operational for RCMSAR and other organizations to train on by the end of June. RCMSAR's head office recently purchased the former Glenairley waterfront estate in East Sooke on Vancouver Island. Having completed SARNav 1, I can attest to the fact that training is both challenging and fun. When you are inside you totally forget you are in a simulator.

While I haven't covered absolutely every piece of electronics aboard I'd be remiss not to mention the automated external defibrillator (AED) we keep in the forward cabin. This is arguably one of the more important electronic devices we have on board and every crew member is trained to do cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and use the AED. CPR buys time until an AED or advanced medical intervention (drugs) can restore a normal heart rhythm. In practice doing CPR and using an AED on a rescue vessel in rougher weather is extremely challenging. In an emergency our primary goal is to get the patient to a higher level of care as quickly as possible.

While I haven't covered absolutely every piece of electronics aboard I'd be remiss not to mention the automated external defibrillator (AED) we keep in the forward cabin. This is arguably one of the more important electronic devices we have on board and every crew member is trained to do cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and use the AED. CPR buys time until an AED or advanced medical intervention (drugs) can restore a normal heart rhythm. In practice doing CPR and using an AED on a rescue vessel in rougher weather is extremely challenging. In an emergency our primary goal is to get the patient to a higher level of care as quickly as possible.

The fourth and final crew member -- seat 4 -- sits behind seat 3 across from a padded bench seat that can carry a stretcher or passengers. On-scene this person will usually work the aft deck with the seat 3 crew member. Their other primary job is to keep accurate log keeping (pen/paper).

Hopefully you'll never need us but if you do you'll be glad the thousand plus RCMSAR crew members are highly trained with some of the best SAR equipment available. Volunteer members are standing by 24/7 ready to risk life and limb to save those in distress on Canada's west coast.

A special thanks to our amazing maintenance officer Boudewijn Neijens for the diagrams and reference material used for this entry.

Share

Share

Thanks, Adam! I think that recreational boaters -- particularly ones with fast boats, and/or venturing out in limited visibility -- can learn from the team approach developed by SAR organizations like yours.

It's interesting, though, that the very capable Flir/Ray T453 dual thermal/daylight pan/tilt/zoom camera system doesn't seem to get used much. I suspect that would be different if it was integrated with an MFD system that could "slew to cue" it to radar targets, AIS targets, etc. Maybe even an AIS MOB device attached to the datum buoy? More on slew to cue here:

https://www.panbo.com/archives/2013/10/flir_m-series_nav_cam_test_raymarine_integration_appreciated.html

Flir PTZ cameras do this integration now with Garmin, Furuno, and Simrad MFDs, as well as Raymarine's current models.